Taking “the will of the people” seriously.

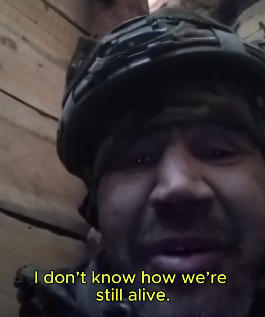

The only case left for Brexit, it seems, is the “Will of the People”, as democratically expressed on 23 June 2016. There will be no manna raining down from heaven, no £350 million per week for the NHS, no have-your-cake-and-eat-it. Now the best an ardent Brexiter like Liam Fox can promise is that we will survive Brexit.

What is the “will of the people”? Should we follow it? Was the EU Referendum an expression of the will of the people? Such questions are rarely asked. Yet answering them is vital, given that the will of the people has become a main argument for going through with Brexit. For instance, Owen Jones argued that he, like many others, "regret[s] the referendum result but in the interests of democracy it must be respected." However, implementing the referendum result is only one way to interpret "respecting the result"*.

The political philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) developed the concept of the will of the people, or as he termed it, the general will. Citizens come together to determine legislation, and this legislation forms the will of the people. Rousseau believed that this way of ruling was preferable to outsourcing it to others (for instance, an absolutist ruler or members of parliament), because people would then not be able to govern themselves.

Note though, that UK parliamentary democracy has not ceased to exist. The UK has not now become a direct democracy. Parliament has been, and is still sovereign, as the Brexit white paper affirms.

As Rousseau argued, certain conditions need to be met for a vote to count as the Will of the People.

The vote must accord with the genuine interests of the people to count as Will of the People

Under some interpretations of Rousseau, the will of the people is in fact the genuine interest of the people: it is what people would want if they were in full possession of all the relevant evidence, and if they carefully thought about the question. Rousseau thought people would imagine what would happen if a new legislation would be adopted for their own personal lives. They would then be able to make an assessment of whether or not they thought it would be a good idea to adopt the legislation in question.

Was this the case for the Referendum? It is very doubtful. Indeed, the Referendum campaign both by Remain and Leave, but especially by Leave, did not offer a realistic picture of what Leave would look like. Leave campaigners promised we would not be leaving the single market. The NHS would be properly funded. Turkey was set to join the EU, flooding the UK with migrants if the UK did not leave the EU. Or, from the Remain side, people were warned that there would be immediate economic catastrophe.

This debate was of poor quality and did not allow people (many of whom had very limited knowledge of the EU, let alone of the single market, customs union, European Court of Justice or what a Free Trade Agreement is) to make a well-informed decision. Compare this to Switzerland, which has a semi-direct democracy with legislative referenda, which requires extensive political education at schools, with information provided by the government in a clear, factual tone, for instance, about the EU (of which Switzerland is not a part) and the bilateral agreements with the EU.

The legislation must affect all citizens in a similar way

A second condition for a popular vote to count as the Will of the People is that there needs to be sufficient similarity in the population such that the effects of legislation will apply to all in the same way. As Rousseau expert Chris Bertram writes

Rousseau argues that in order for the general will to be truly general it must come from all and apply to all…For this to be true, however, it has to be the case that the situation of citizens is substantially similar to one another. In a state where citizens enjoy a wide diversity of lifestyles and occupations, or where there is a great deal of cultural diversity, or where there is a high degree of economic inequality, it will not generally be the case that the impact of the laws will be the same for everyone. In such cases it will often not be true that a citizen can occupy the standpoint of the general will merely by imagining the impact of general and universal laws on his or her own case.

Brexit will not impact everyone equally. Let's look at one example: richer people are much better insulated against any adverse effect of Brexit than poorer people. As I am writing this, 1 GBP = 1.09 EUR. Before the EU referendum, 1 GBP = 1.29 EUR (a bit down from before, due to the uncertainty of the Referendum). Inflation is up. Interest rates are cut. This is obviously a much bigger challenge for someone who earns a low wage, struggling to meet the end of the month, than for someone who has assets and a high wage.

The people most affected by a referendum must have a say in it

Third, for a vote to genuinely be the will of the people, it should be the case that all people affected by the Referendum, who are in a position to vote (so not small children, for instance) should have a say in it. The people most affected by Brexit, EU citizens living in the UK (with the exception of the Irish) and UK citizens living in the EU for over 15 years, were disenfranchised from the Referendum, unlike Commonwealth citizens. Negotiations about EU/UK citizen rights are still ongoing, but it is presently looking that both will lose substantial rights they enjoyed before. And a no deal scenario on their rights is still possible.

One could object to this line of reasoning by arguing that the Referendum simply adopted the franchise of parliamentary elections and was therefore "democratic".

However, general elections aren't referenda. Parliament does not require the will of the people to adopt a specific legislation. Rather, people vote to elect MPs who will vote about legislation, taking into account the best interest of their constituents. Crucially, constituents also include people who cannot ordinarily vote, including children, EU-27 citizens, non-commonwealth non-EU citizens, prisoners, and UK citizens who left for over 15 years (their MP is the one of the last constituency they lived in).

So even though these constituents do not have the right to vote in general elections, they do have their interests represented when legislation is adopted. But that is not the case with a binary referendum in which they have no say. For this reason, Scotland chose to give everyone over 16 who was a long-term reside a vote in the Scottish independence referendum, making their referendum a much better reflection of the Will of the People.

Avoiding the tyranny of the majority, hysteria, and using referenda for own political gain

Fourth, the will of the people must not descend into the tyranny of the majority. Referendums have winners and losers, and this Referendum was very close, at 51.9 vs 48.1. In such a situation (as in any referendum) there is a risk that the majority crushes the interests of a minority. Moreover, it is possible that, as Talmon worried,

the excitement of the assembled crowd may exercise a most tyrannical pressure, and that the extension of the scope of politics to all spheres of human interest and endeavour, without leaving any room for the process of casual and empirical activity … the shortest way to totalitarianism

It is certainly not an imaginary concern that referendums can be used to whip up hysteria that prevents cool deliberation, or that they are misused by leaders (such as Erdogan) for their own political gain. But even if that doesn't happen, there is still the worry of the tyranny of an — as Talmon worried — irrational majority, willing to inflict significant damage on the economy, including job loss for family and friends, to have their Brexit materialised.

What are the wishes of Remain voters? Remain voters are concerned about losing their right to work, study, and retire in 27 other countries, they want to retain the benefits of the single market, protect worker's, consumer's and environmental protections, and they don't want to jeopardize peace in Europe (including in Northern Ireland).

Although Remain lost the EU Referendum, it is still possible to go ahead with Brexit in a way that respects or at the very least acknowledges their interests. Indeed, the fact that even a majority of Leave voters would be willing to pay for EU citizenship indicates that this is plausibly part of the general will. In spite of British citizens' enthusiasm (including Leave voters) for continued individual EU membership, the UK does not have the retention of rights afforded by EU membership as a negotiating objective*. It is rather ironic that the main initiative to help UK citizens to retain their EU citizen rights comes from the EU, e.g., Guy Verhofstadt's (unsuccessful) initiative for a paid associate membership status.

Note, as a useful contrast, the Good Friday Agreement, which phrased the opinion of the minority for an Irish union as follows. The parties to the agreement:

…acknowledge that while a substantial section of the people in Northern Ireland share the legitimate wish of a majority of the people of the island of Ireland for a united Ireland, the present wish of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland, freely exercised and legitimate, is to maintain the Union and, accordingly, that Northern Ireland’s status as part of the United Kingdom reflects and relies upon that wish; and that it would be wrong to make any change in the status of Northern Ireland save with the consent of a majority of its people.

This phrasing is interesting because it acknowledges the wishes of the proponents of a united Ireland as "legitimate" but it also says that because the majority of Northern Irish prefer the Union, the only way to change the status of NI is through majority consent (presumably, a future Referendum).

By contrast, the UK government does not even acknowledge that a substantial minority (nearly half!) of eligible voters voted to Remain. For instance, Theresa May's Lancaster Speech starts as follows "A little over 6 months ago, the British people voted for change." — there is no mention of those who did not vote for change but who preferred the status quo.

In sum

We do not bring a country together by ignoring the wishes of the minority, some of whom are "crying themselves to sleep" with worries over Brexit. We cannot expect "loser's consent" to do all the work that a genuine democracy is supposed to do. Committed Remainers are accused of moaning or trying to sabotage the Brexit process, but without the government considering any of their concerns, what incentive do they have to make Brexit work? Taking the will of the people seriously means taking the interests of minorities, the disenfranchised, and the ones who lost, seriously too.

*As Rebecca Bamford has argued, there are several ways in which we could respect the referendum result, other than leaving the EU.

*One might argue that the UK does not have this as a negotiation position because they think it is an unrealistic objective. However, the current UK negotiating position has many objectives that are a stretch and probably unrealistic to achieve, for instance, its wishes for a transitional customized customs union.